The cost of Romance fraud

How romance fraud is becoming a major financial crime and what is being done to fight it

Social media and new technologies are making it increasingly easy for fraudsters to operate romance scams, often on a massive scale.

Innovative solutions are necessary to protect people from this most personal of crimes.

When the head of economic crime at UK Finance, the national trade association for banks and financial institutions, says the rise of romance scams is a serious concern, it’s time to take note.

“Measured in financial terms, it’s a huge and growing problem,” says Ben Donaldson. According to UK Finance figures, in the first half of 2023 romance scams cases were up 26 per cent year on year, while the City of London Police said such scams netted fraudsters £92.8m in 12 months between 2022 and 2023. “That’s just the tip of the iceberg. That’s just reported crime. The actual figures will be far higher,” he says.

Also known as catfishing, this type of fraud, where swindlers form relationships with members of the public for their personal gain, doesn’t just have a financial cost. All too often, the reaction to those who have fallen for a romance scam is one of blame. Some victims have lost friends and even relationships with family members. And most tragically, some have taken their own lives.

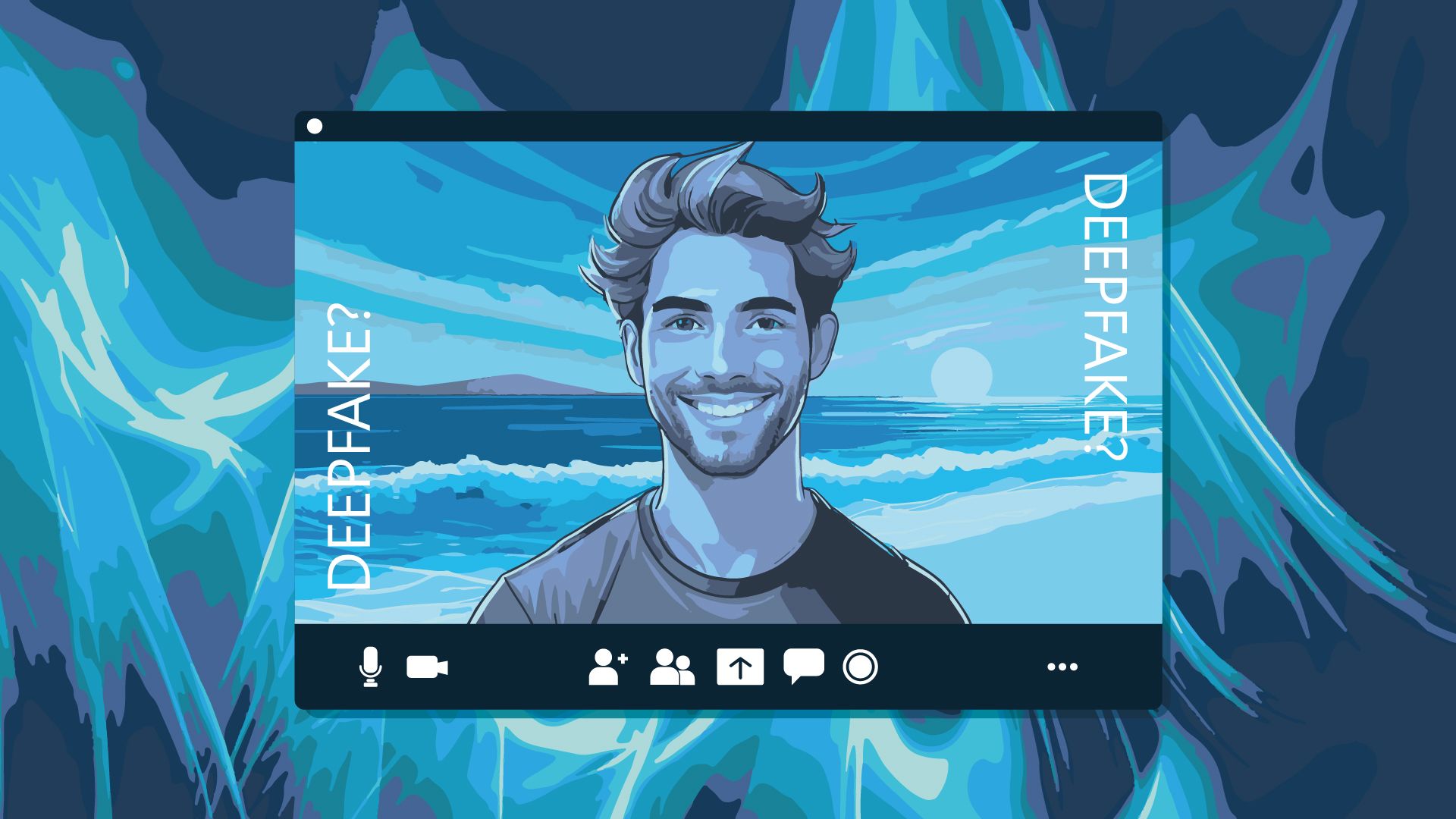

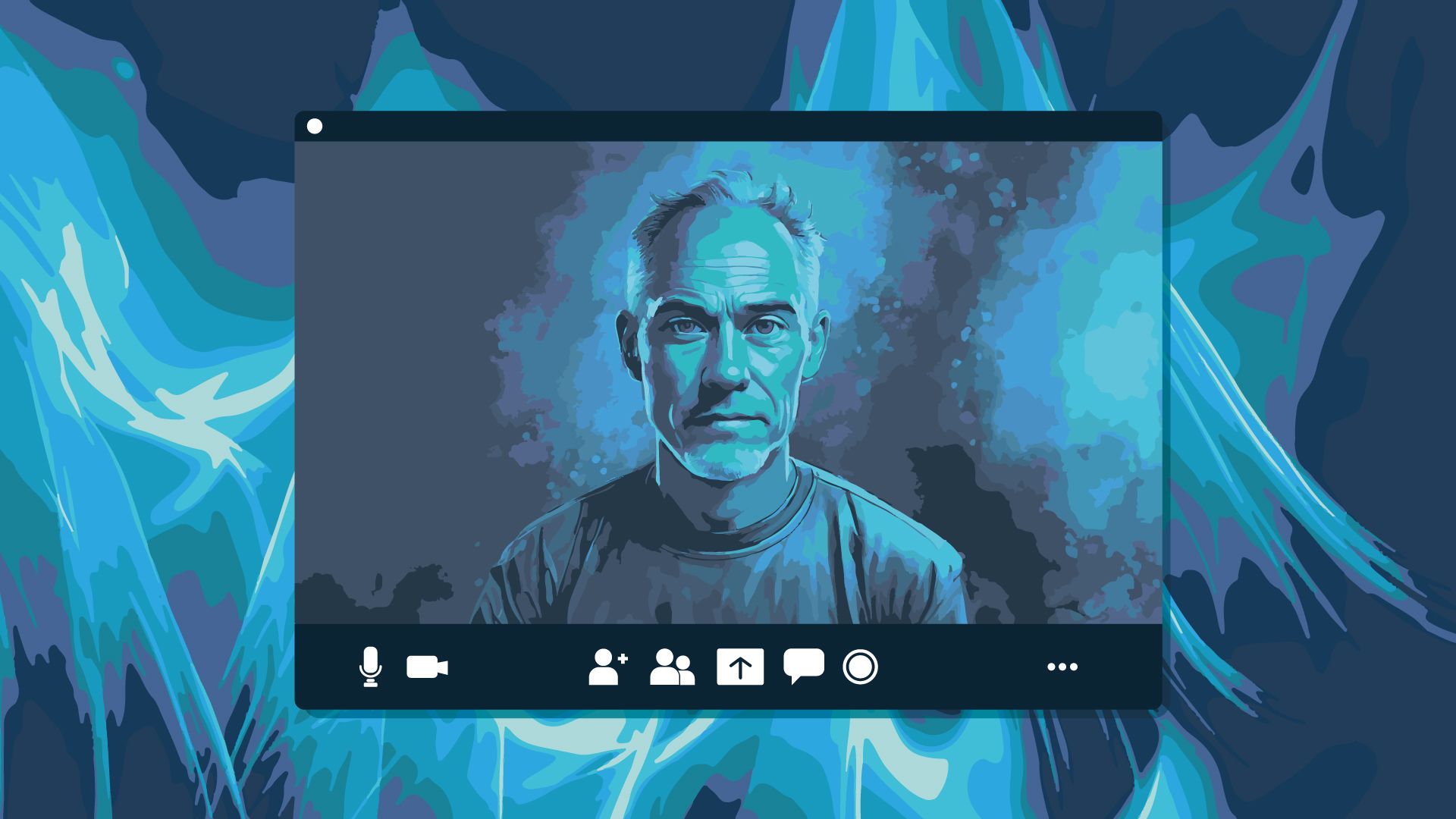

But the truth is anyone can be scammed. Rich, poor, young, old, men, women. They’re all seen as fair game by the conniving criminals and con artists who hone their modus operandi, research their targets on social media and use the latest technology — increasingly including generative AI and deep fakes — to dupe their targets.

As the problem has grown, activists, banks, authorities, and analytics companies have stepped up efforts to combat it. Victims are increasingly willing to go public, helping to dispel the shame and stigma, while police forces are running awareness campaigns and successfully prosecuting more perpetrators. The UK’s Online Fraud Charter is breaking new ground with a voluntary agreement between technology companies and the government to stop fraud on their platforms. Meanwhile, banks are looking at how they can better equip themselves to spot payments being made under false pretences and train their staff accordingly. Analytics companies are collecting data intelligence and creating machine-learning models that will help them.

Tech-enabled predation

Francesca C (not her real name) is a successful professional fundraiser who has raised tens of millions of pounds for charities over the last two decades. In her early sixties, she’s smart, confident and looks far younger than her age. Taken together, not the attributes of someone easily conned.

“These people are clever and manipulative. They know how to work on you. I’ll never forget how he made me feel like the most special person in the whole world in the first month,” she says.

Her seducer called himself Peter Wilson on the dating site Match.com. He told her he worked for Shell on oil rigs. Flirtatious, complimentary, interested, intelligent, he seemed the real deal.

They moved their chat from the dating-site app to Viber, a free, untraceable messaging and phone app, with Wilson always initiating the calls. When Francesca queried this, he said it was oil-rig protocol.

She believed him.

After just four weeks, he rang to say his bank account had been hacked, he couldn’t access it and would Francesca lend him £2,000.

She agreed.

Within three months, she’d scraped together another £118,000 to lend him. His supposed needs varied from having to pay his parents’ healthcare bills to legal fees. So keen was she to help, she got the cash by borrowing from friends, promising to pay them back when he repaid her. And when she queried his needs, he went silent – a common scammer tactic to hurt the target in order to draw them in further.

That was six years ago. Today, Francesca admits she had had inklings that Wilson wasn’t who he claimed to be, but she ignored them, as well as friends’ warnings, and continued to send cash.

“I desperately wanted to believe him because if I was being duped, I was being financially and emotionally ruined,” she admits. It was only when she went on to the Shell website, saw a warning about romance scams, spoke to its HR department and was told there was no oil-rig worker called Peter Wilson that she admitted the truth.

A fraudster shows how lucrative this crime can be

A fraudster shows how lucrative this crime can be

She cashed in some of her pension and took a second mortgage to repay her friends, who then ditched her. When she asked her brother for help, he refused, leaving in tatters another relationship that had been close. These reactions put her off approaching her bank. “They made me think I was a silly woman who deserved what I got,” she says.

Eventually, she did tell her bank and, via the ombudsman, got her money back with interest. “I had to do a lot of work. It wasn’t easy,” she says, adding that the bank hadn’t raised a single query about any of the payments – despite their size and overseas destination. Unbelievably, Peter Wilson’s profile can still be found on dating sites, so Francesca presumes he is continuing to scam women.

Spotting the signs

These scammers aren’t always after money. For a minority, it’s a power play to get people to have sex with them – under false pretences.

Anna Rowe is a primary-school teacher. The beautiful, smart, tenacious and independent mother of two fell for Tony on Tinder in 2015. He told her he was divorced, looking for love, that he was trustworthy, honest and genuine. They became lovers and had a relationship for 14 months.

The trouble was, he was married and simultaneously pursuing other women – Rowe has found four others he was similarly lying to while she was seeing him. Although Tony had never asked for money, she says he followed the scammers’ playbook.

“At first you have the grooming, then the love-bombing. And then the trauma bonding,” she says, explaining that Tony had told her his mother had terminal cancer and how hard his divorce had been.

When she went to the police, she was told he’d done nothing against the law. Their response turned her into an activist. She started the website Catch the Catfish, with information about how to stay safe when online dating, and co-founded Love Said, which supports those caught up in love scams. She also wants the law tightened so men like Tony who groom women for sex can be prosecuted and has a petition with more than 53,000 signatures.

More recently, she’s given evidence to the Home Affairs Committee’s new inquiry into fraud. “It’s very easy to identify this grooming. The emails and texts are there in black and white. And the pattern is very easy to see,” she says.

Under current legislation, there’s not much the police can do for people like Rowe. Detective constable Rebecca Mason, who specialises in romance scams, couldn’t be more sympathetic, but is clear: “It only comes under fraud if money is involved. Lying isn’t illegal. And it’s not a crime to fall in love and give people money.”

Like Ben Donaldson of UK Finance, she’s also concerned that love scamming is an under-reported and growing problem. “I think more people are involved. Social media and dating apps make it so easy for them to contact people. I get messages asking what victims should do. The stigma of reporting it still exists.”

She admits this has been exacerbated by the response some have received when they’ve gone to the police. “It varies from force to force, even cop to cop. The resources aren’t there – like in any area of policing,” she says.

However, things are changing. The police are running campaigns, including one called It Wasn’t Your Fault, and are successfully prosecuting more people. In the past few months these include David Checkley, who conned at least 10 women out of £100,000 and was jailed in November for 11 years, and Sebastian Timmis, who stole more than £30,000 from women he met on dating sites and was jailed in January 2023 for 38 months.

Easy pickings

Still, progress is slow, as the numbers keep on growing. According to Donaldson of UK Finance, more fraudsters are turning to romance scams because it’s easy.

“The payments industry has invested heavily in applying controls to protect customers from unauthorised payment fraud. However for authorised push payment fraud, as the account holder initiates and, when questioned, confirms the payment this adds a layer of complexity for firms to detect the payment as a fraud,” he explains.

He also believes that criminals are increasingly drawn to it because social media and dating apps provide plenty of opportunity to research potential targets – the attack vector. “It all just makes people so much more accessible,” he says.

Such easy pickings have attracted organised crime, particularly in West Africa. So bad has it become that the US embassy in Ghana has issued warnings to US citizens worldwide. Experts like Donaldson believe the problem will only get worse thanks to rapid advances in technology such as generative AI and deep fakes.

Deep fakes allow the criminal to construct video images of a target’s ideal lover, again using social media to do the research. They’re so successful that gangs even enslave people to do the scamming for them on an industrial scale; governments across South-East Asia have been raising the alarm about criminal organisations luring unwitting job seekers into “fraud factories”.

Given most love scams start online, Donaldson is pleased to see the adoption in the UK last year of the Online Fraud Charter, and that Tinder has recently introduced an identity verification scheme in the UK and a number of other countries. But he does believe more is needed.

“If people on social media had to verify their identities, that could be a real game changer,” he says. He also wants banks to share more information and adopt technology in a more defensive way. “Information and intelligence sharing is one of the things that we’re very keen on. The more banks share, the fewer refuges the criminals have.”

But educating the public and training key staff also remain major focuses for UK Finance. “We run a consumer awareness campaign called Take Five to Stop Fraud, to educate the public on how they can protect themselves from fraud. As part of this, we conducted research which found 18 to 25 year olds were being targeted on social media. One of the things that made them vulnerable was misplaced confidence that they would never fall for a scam,” Donaldson explains. The organisation also oversees a collaborative initiative, called the Banking Protocol, to provide a rapid response to consumers where bank staff spot warning signs that a customer is falling for victim of a scam. Since its inception the scheme has stopped in excess of £320m in scam payments and facilitated approximately 1,400 arrests.

Nevertheless, Donaldson accepts it’s always going to be hard. “It’s striking the balance between protecting people and enabling them to do the things they want to do with their money. That’s a big challenge,” he says.

New models for fraud detection

This is where technology can play a vital role. Banks have already put in a lot of defences against fraud, whether that’s detection models looking for digital intelligence to identify suspicious activity or extra layers of authentication and confirmation. But with romance scams, it’s the genuine account holder who authorises the payment, so banks need to find new methods of spotting suspicious behaviour.

Stephen Topliss, vice president of global fraud and identity at LexisNexis Risk Solutions, part of RELX, puts it like this: “Banks have got to create new fraud models that look at authorised fraud, look to see what signals can be used to detect whether it’s a scam.” These include the way the customer logs into their account, sets up a new beneficiary and makes payment. “These things all tend to be a little bit different when there’s a scam. The customer may be hesitating, or more emotional. This affects timings. It's what we call behavioural biometrics analysis which allows banks to respond as needed to a customer's behavioural anomalies. But we also need to look where the money’s going.”

The involvement of interconnected networks of criminal gangs operating on a global scale raises the probability that the destination account will be a mule account owned by someone being paid to receive and then send on the cash. Here alerts can be raised if larger than normal sums are passing through, or even if there’s a higher number of payments in and out.

LexisNexis ThreatMetrix, a digital identity intelligence and digital authentication solution from LexisNexis helps banks do this. But for the software to work at its best, it needs masses of data. “We need to have different types of data than maybe banks historically collected,” Topliss says. “Part of our job is to help banks understand all the things they could bring to make the models successful. That includes data from different parts of the bank – fraud and money laundering have traditionally been handled by different departments. In romance scams, there can be a connection.”

Another way Topliss and his team get more data is through the LexisNexis Digital Identity Network, a consortium capability which aggregates anonymised transaction data such as logins, payments and new account creations, and helps distinguish between trusted transactions and fraudulent behaviors in near real time. The solution is a contributory platform from across different industries including retail, banks, telecom and gaming. “This allows them to work together with confirmed fraud or scam data,” he explains. "The best way to tackle complex global crime is by using the power of a global shared network."

Despite the international growth of romance scams, Donaldson of UK Finance points out that unfortunately many countries aren’t measuring them, so it is impossible to determine the true scale of the problem. But he knows that there are many more victims out there, often suffering in silence.

“Romance scams are a particularly nasty crime that has not just a financial aspect but causes huge psychological damage, too. At UK Finance, we’re almost the last step in the crime. We need everyone involved to play their part. That would really make a difference,” he says.

Resources

Need help?

Go to Lovesaid.org for support and resources

Dating online?

Go to Catch the Catfish for advice and blogs about online dating, romance fraud and a list of useful websites

Safe dinner date guide

Starter

Check the photos on facecheck.id and other reverse image searches

Main

Do they want you off the app quickly? Moving to another app with speed is a sign of a predator or criminal

Dessert

Is the connection moving quickly? That immediate soul mate connection should be cause for concern

Drinks

At the beginning and throughout the relationship, get a friend to look over their profile and their story. Fresh eyes can be helpful when you’re feeling caught up in a whirlwind