Missing, vulnerable and exploited

Recovering America’s runaway children

Around 1,000 children go missing every day in America, many lured by criminals who go on to victimize or harm them.

We need to wake up to this tragedy so we can do more to prevent them leaving and to help them if they are in danger.

When kids go missing today, they have usually run away. Most are running away from something they’re struggling with and increasingly they may have been groomed to do so by opportunistic criminals.

Last year, the FBI registered 359,094 reports of missing children. The non-profit National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC) says that of the child disappearances reported to it in 2022, runaways accounted for 91 percent.

These distressing figures do not change much from year to year and those working in the field say the true numbers may be even greater, as many children who run away are never reported missing.

Experts are now pushing for a fundamental change in awareness around the issue, and for holistic, coordinated action to tackle it at a national level.

While fears of abduction loom large in the public consciousness, today children are rarely 'kidnapped' in the traditional sense by strangers.

The sad reality is that kids are more likely to be groomed or tricked to leave home by predators who see children as a commodity to be exploited.

Increasingly, this exploitation occurs on an industrial scale, as evidenced by paid-for online courses on how to pimp a minor and the remorseless cruelty meted out to maximize the profit.

Dr. Michael Bourke, formerly the Chief Psychologist for the United States Marshals Service (USMS) and founder of the USMS Behavioral Analysis Unit, says: “Criminals view selling kids’ bodies as better than selling drugs. Unlike drugs, you can keep reselling the same child over and over, 10-12 times a day or night.”

The public also too often sees runaways as 'bad kids from bad homes' and blame them for their predicament. In fact, criminals may target and manipulate children from anywhere — good, broken or foster homes; wealthy or poor families, documented or undocumented.

A complex issue

Marty Kemp, the First Lady of Georgia, works to raise awareness of child trafficking through the Georgians for Refuge, Action, Compassion and Education (GRACE) Commission, which she founded with the support of her husband, Governor Brian Kemp.

The scale and complexity of the issue demands it be treated as an urgent national concern, with recognition by society that such kids are in no way culpable for and complicit in their fate. They are children who have been tricked or are running away from some kind of trauma — in many cases both.

The runaway reality

“Based on my experience, 75 percent are fleeing from some type of abuse, instability or maltreatment in their home environment,” says Jackie Goldstein, Forensic Interview Specialist at the US Department for Homeland Security (DHS), who has been working with vulnerable children for nearly 20 years.

Ana Cody, Section Chief at the DHS and expert on the issue, adds that they may be experiencing complex challenges that impact their mental health. “These young people face multiple adversities in their lives that make them feel stressed, depressed, isolated; and they may also have suicidal thoughts. They do not have the tools to cope with these situations. They run away thinking that things will get better,” she explains.

But life on the street is horrific.

According to NCMEC, one-in-six runaways are likely victims of sex trafficking and the average age at which children are first trafficked is just 15. Wellspring Living, a non-profit organization based in Georgia that provides services for domestic sex trafficking victims and those at risk, estimates that 100 minors are sold for sex every night in its state alone. And as Bourke says, these children aren’t just sold once a day; they are sold repeatedly: “They even put victims in ice baths so they can continue to engage in sex acts.”

Trafficking children today has become an industrialized criminal enterprise. While the playbook of promises used by the predators might seem unbelievable to those lucky enough to have stable lives, to vulnerable children it’s just what they want to hear — offers of freedom, friendship, money and even glamorous jobs.

“Bad people are recruiting them for modeling positions and modeling jobs. Let’s be clear. They are tricked and groomed by criminals.”

Barriers to help

Just as society doesn’t see runaways as vulnerable children, many young people do not see themselves as runaways. As Cody explains: “They think, well, I was in a bad situation and I did not like what I was experiencing, so I left.” Once on the streets, these young people are victims of multiple victimizations, including commercial sexual exploitation.

Society’s lack of understanding of the issue translates into there being little information directed at vulnerable youth, including youth who are on the run or their peers. If children do not see themselves as runaways, or do not know where to seek help before or after running away, they do not know that help is available. “We really lack resources to prevent run away incidents and messages that youth can relate to,” says Cody. For youth from underserved communities and those with language barriers, things are further complicated.

And as time passes, it gets harder to help them. They may travel out of state, but other factors can also play a part in locking them into their plight.

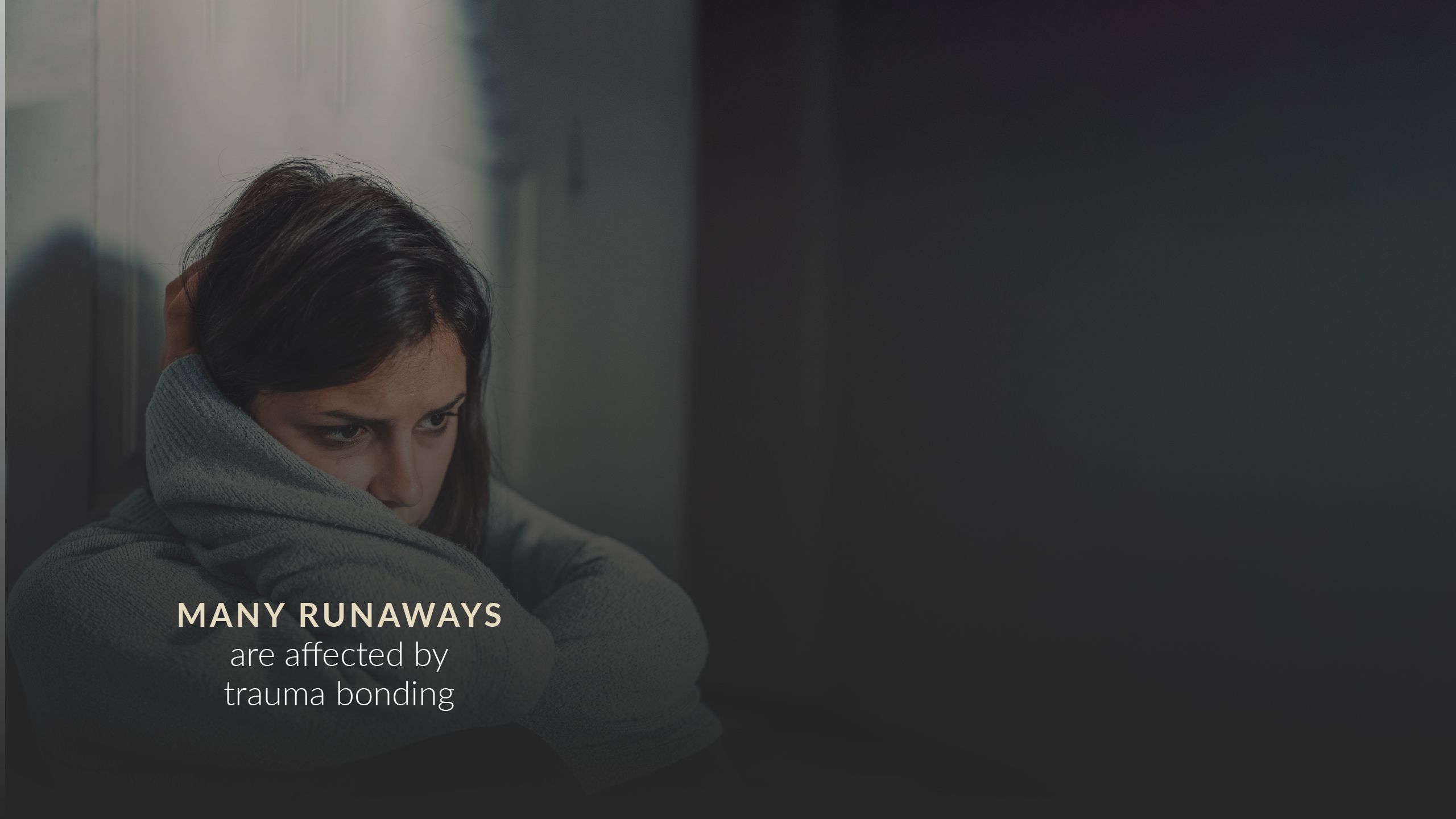

Trauma bonding affects judgment.

Trauma bonding happens when the children become attached to or reliant on the people who traffic or abuse them. This bonding can stop them from seeking help as can their fear of the consequences of doing so.

This phenomenon is often seen by those working at Wellspring Living. As Delton MaGee, a Director at Wellspring Living, explains: “All youth, especially youth of color, may have an unhealthy fear of what will happen to them and what they’ll be charged with if they do turn to someone for help. And the trafficker manipulates that fear.”

Bourke recounts: “One boy, who was sexually assaulted every single day, violently for many years, actually posted on the website his parents had set up to help find him: ‘If you found him, would you even want him back?’”

Blaming the victims

All of these issues are compounded by the social stereotyping of runaways. “There’s automatic blame that they are responsible, that they asked for this in some way,” says Cody.

So prevalent is this view that even some within law enforcement have been known to get it wrong. Thankfully, this is changing and many law-enforcement officers today attend awareness courses that are helping to find these children.

“One young girl, lured from home by criminals posing on Facebook as friends to go to concerts with and subsequently trafficked for sex, was found when a state trooper pulled over a car because of an expired registration. The officer asked for the driver’s license but was handed three sets of documents — for everyone in the car. This was a real red flag. He got everyone out of the car, giving the girl the chance to speak. That’s how she was found,” Goldstein of the DHS recounts.

It's difficult to change perceptions.

But according to Georgia’s First Lady Kemp, changing perceptions and ending stereotyping is hard, particularly when there’s a lack of public and official acknowledgement of the problem itself. She says this feeds into the media, which doesn’t give it the attention it deserves. “A lot of media have done interviews with me and then don’t even run the story.”

Without public discourse, people are left not recognizing the warning signs that a child is at risk. “We just had a case in Georgia where a girl ran away and was walking on the highway. Thousands of people went by her, on this major highway. And somebody picked her up and then traded her to a man for drugs. He just gave her away,” says Goldstein.

Worryingly, some establishments are also complicit. In Bourke’s experience, hotels, for example, where victims might be trafficked, will intimidate staff into not reporting their suspicions. “I met one bellhop who told his manager about a situation and was told to shut up and not ever bring it up again or he’d lose his job,” he says.

Toward holistic action

Thankfully, there are excellent national and local organizations that help find and support runaways. The National Runaway Safeline offers help to runaways and homeless youths, their parents and friends, as well as to teens in crisis. NCMEC and the ADAM™ Program, in partnership with LexisNexis® Risk Solutions, also offer help. Independent and state or local initiatives like Wellspring Living provide safe accommodation to children who have been trafficked. Wellspring Living also runs partnership-in-prevention programs with hotels, schools and sports venues while the GRACE Commission organizes awareness training programs.

This means looking at runaway incidents as a public health issue. “We need to treat it holistically, prevent it, educate youth and the public, develop the right policies and increase awareness that these kids need our support,” she says.

This starts with spotting red flags.

Some might be found by looking at children’s activities on social media. One recent TikTok trend, for example, encouraged children to run away to see how many likes they could get on posts searching for them. And Bourke warns that social media and gaming platforms are used by predators to groom vulnerable children: “We definitely need to do a better job of educating parents about harms online, about grooming.”

Learning where to look

Christian Murphy, Deputy Director at Wellspring Living, points out that kids trafficked for sex may be tattooed or branded by their trafficker, so tattoo parlors should be contacted and recruited as lookouts. Equally, trafficked children are often given small-value rewards such as clothes, shoes, hair weaves and fast food.

Such places should also display information about the available help in terms and in a language they will understand and relate to. And we should learn to pay attention to children seen out late at night or heading into inappropriate facilities such as strip clubs or bars.

Alongside ditching the blame and taking a victim-centered approach, more safe houses like Wellspring Living and The Receiving Hope Centers are needed.

“If we could train and make aware those working in shopping malls, beauty parlors, McDonald’s and Applebee's in what to look for we could find more kids.”

Delton MaGee and Christian Murphy of Wellspring Living

Delton MaGee and Christian Murphy of Wellspring Living

But on their own, these efforts are not enough.

They need to be supported by appropriate policies and well-drafted legislation. Current data laws make it hard for different agencies to use data to do their jobs, experts say, while reporting requirements and investigation procedures need to be strengthened in many cases.

In Florida, for example, a hotel must report suspicions that a child is being trafficked on its premises. More than 7,000 citations have been issued to date, but not one hotel has been fined. Bourke explains the loophole: “As long as the hotel says the problem has been fixed, the report goes off the record. That is now being changed.”

Some states are beefing up their legislation — besides Florida tightening up hotel regulations, Georgia has also recently introduced harsher penalties for the perpetrators, such as lifetime bans for any truck driver found involved in child trafficking. But at a national level more work needs to be done.

A new community mindset

A child is brought up by a community, not one family, parent or caregiver.

We, the community, need to take more responsibility for the terrible number of runaways seen across the U.S. "We need to pay attention to these kids and the factors that may cause them to run away, such as abuse, neglect, family violence and mental health," says Cody. "We need to equip them with tools and resources and encourage them to seek help when needed. Communities need to start seeing them as children who need our support instead of 'bad' kids."

We need to check out our children’s online activities and encourage them to talk, not just about their own experiences, but also those of their peers who might be at risk. And we need to emphasize that there is no question of wrong-doing or blame. Bourke is adamant: “Removing blame eliminates the onus for interpretation — if this meets the criteria of illegal, bad or wrong. The child shouldn’t be the one making that decision. Removing that alone would solve many issues. It would nip it right in the bud.”

Finally, we must learn to take notice of suspicious situations and act upon them — doing so might save a life.

“You don’t need to be sure somebody is being trafficked to make a report. That’s law enforcement’s job. But if you don’t make that report, we might never have the opportunity to look into it.”