Billion dollar crime

The devastating financial and personal costs of romance scams

No one is immune to the sophisticated, psychological con that is increasingly being run on an industrial scale

There’s an image Beth Hyland has of herself when she was deep in the grips of a romance scam that she still finds hard to process. In it, she stands in front of a Bitcoin ATM feeding in crisp one hundred-dollar bills. The cash is from a loan she has just taken out and, over the course of several days, Beth will insert $26,000 into the machine. The money is headed to the cryptocurrency wallet of a man she has never met, a man she believes she is engaged to, who may or may not be in Qatar.

...what’s more, the transaction is Beth’s idea.

Such is the manipulative power of the well-orchestrated romance scam, a criminal enterprise so sophisticated and psychologically nimble that it's able to steal the life savings of its victims—all in the name of love. The perpetrators are skilled and ruthless, preying on people regardless of age or gender. No-one, it seems, is immune. Yet when sufferers muster the courage to report what has happened, many are told that not only is it not a crime, it's likely their fault.

In 2023, over 64,000 people reported a romance scam to the Federal Trade Commission’s Consumer Sentinel Network, for a total reported amount of $1.14 billion stolen. That’s up from $493 million in 2019. But most romance fraud is not reported. Erin West, a California cybercrime prosecutor and founder of Operation Shamrock, the first national coalition against the “romance confidence scam industry,” estimates upwards of $10 billion a year is now being stolen in the newest form of romance and relationship fraud involving cryptocurrency investment, sometimes referred to as ‘pig-butchering’.

“We've never seen a wealth transfer like this. We've never seen victims as devastated as this,” she says of the recent explosion in this type of fraud. “It’s an epidemic. It's a worldwide catastrophe that nobody is really working to control.”

West has appealed to Congress to appoint a Scam Czar to tackle the “transnational organized crime epidemic” of romance fraud involving cryptocurrency schemes, which lures victims into fake investments with the promise of high returns and often strips them of everything. Calls are meanwhile growing for a coordinated, multi-agency response involving all from law enforcement and banks to social media platforms, analytics companies and advocates for victims. “It's a crime that seems to lack a lot of empathy from others, but it is devastating,” says West, who has been stunned by the numbers left suicidal after their life savings are stolen and they fail to find help.

Falling in love with fakes

Like many victims, Hyland’s ordeal began with a fake online profile, a man calling himself Richard Daub who she matched with on Tinder in October 2023. “He was everything I was looking for,” recalls Hyland, a Michigan-based administrative assistant. “I’m pretty spiritual and I've done a lot of self-help, and he portrayed himself to be the same way, which really got me.” Soon they were talking regularly on the phone and planning to meet.

“Nothing seemed weird,” she says. “I never thought ‘scammer.’”

Richard, who said he was French and lived in Indiana, showered her with affectionate messages. They even had one brief video call where she could see his mouth moving, which she would later realize had been a deepfake. “Within two weeks, I told him that I had completely fallen in love with him, and he said he felt the same way.”

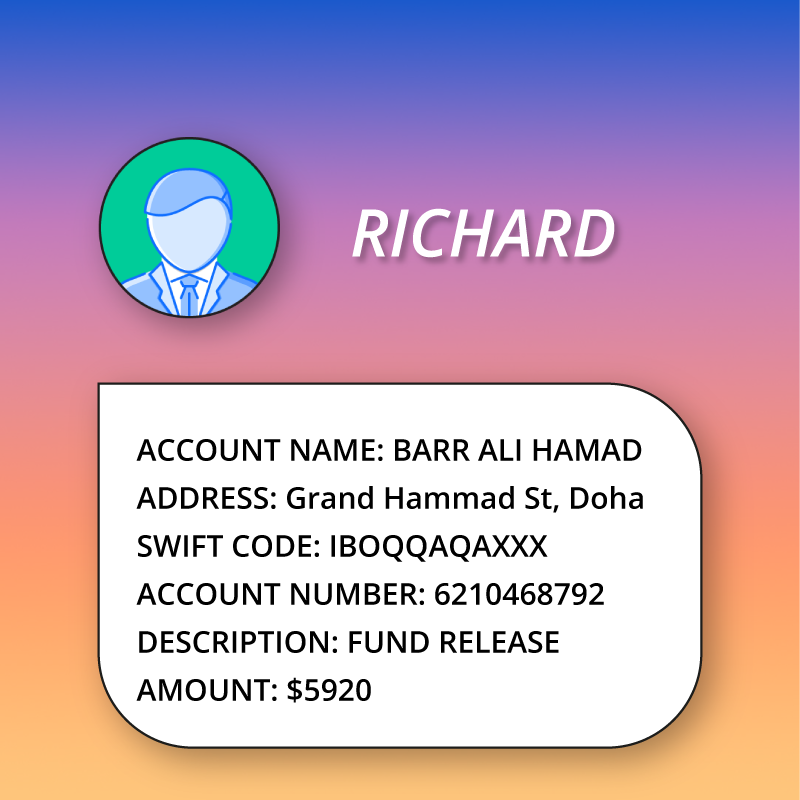

But the meeting never happened. Instead, Richard, who said he worked as a project manager in construction, had to travel to Qatar to collect a “$10 million payout” from a job completed during Covid. “At this point we were unofficially engaged,” says Hyland. So, when Richard asked her to log into his bank account and transfer some money for him, she complied, flattered by his trust.

Then he ran into issues accessing the $21,000 he needed for a lawyer and translator in Qatar. Hyland didn’t hesitate. “He didn't ask me for money, I offered,” she recalls. “In fact, he tried to discourage me. He said ‘no, wait, I'm talking to a friend.’ But then I told him, ‘You know what? I'm going to try to take out some loans and help you out.’ And when I told him, he started crying, saying, ‘no one's ever loved me like this before’ and it all sounded so real. Why wouldn't I trust him?”

She sent Richard cryptocurrency via a Bitcoin ATM, a process that added $5,000 in fees. Then he asked if she could help oversee his $10 million payout, so she signed what looked like a beneficiary form and contacted an “account manager” via WhatsApp. Two days later $10.1 million showed up in the fake account and Hyland was told a $50,000 activation fee was needed to access the money.

Despite her doubts, she offered to ask her financial adviser about accessing her retirement account to get the money. Once in his office, she told him everything. “Looking back, I think it was almost like a cry for help, like something in me knew,” Hyland says. “He and his team are trained in romance fraud, and he said, ‘I think you're in a romance scam.’ I was like, ‘No! We're in love. He would never do this!’ I couldn't believe it, but I couldn't ignore it.”

When she confronted Richard, he denied everything and even doubled down in an effort to continue the con, playing on Hyland's emotions to guilt her into continuing their relationship. When that didn't work, he turned to gaslighting and accused her of being unable to tell fact from fiction. Finally, she did a reverse image search on his picture and “found the real person behind the profile that they stole, a German guy. So then I knew for sure.”

She was left reeling. “I was in shock. I just remember coming home and I curled up on the floor and I cried and cried.” When she reported it to local police, Hyland was told it wasn’t a crime because she had given the money willingly. A year on, she still feels grief and heartbreak but is focused on healing and becoming stronger day by day.

A global enterprise

Many of the scams that target Americans are the work of criminal syndicates based in West Africa or Southeast Asia. There, con artists toil in so-called boiler rooms or scam factories, trawling dating and social media sites for targets, or sending random wrong number texts in a bid to start conversations. Generative AI and deepfakes can lend frightening levels of credibility—face and voice cloning for video calls is common—and scammers often spend months building trust before mentioning money. Increasingly, this comes in the form of enticing cryptocurrency investment opportunities, with the fraudsters even building sleek-looking fake platforms where victims can track their supposed gains. For some, the financial impact is cataclysmic: savings accounts and college funds emptied, retirement plans liquidated, homes remortgaged, millions stolen.

West says: “A lot of haters out there like to make fun of victims of romance scams and one of the things they frequently say is, ‘how could you send your money to someone you didn't know?’ The difference here is you're not sending your money to someone you don't know. What happens is you've fallen in love with someone, they've shown you this persona that is so likable and so charming and seems so well financially established, and then that person offers you the opportunity to increase your wealth. So you are making an investment based on a lot of things that appear very trustworthy.”

For most victims, scams are traumatic, says Cathy Wilson, a Colorado-based licensed professional counselor specializing in the emotional impact of fraud. As well as a huge sense of betrayal, most suffer “tremendous shame,” she notes. Those who go on to report their ordeal are often re-traumatized by “victim-blaming”.

“Frequently, law enforcement won't even take a report and tells them it isn't a crime,” Wilson says. “They are not looking at these manipulation tactics as the criminal weapons that they are.”

Protecting the victims

Advocating Against Romance Scammers (AARS), a non-profit set up in 2016 to help victims and campaign for legal changes, wants businesses and legislators to do more to protect people from what it calls “the cancer of the social media world”. At present scammers openly use platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp as “free office space,” says co-founder Kathy Waters. They even post calls for trainee scammers or fake job advertisements that lure unsuspecting job seekers to scam factories in Southeast Asia.

Waters’ AARS co-founder, retired US Army Colonel Bryan Denny, has spent the past eight years fighting to get sites to remove thousands of fake profiles that use stolen pictures of him, many in uniform. The married father of four first discovered the identity theft when a woman got in contact via LinkedIn claiming to be in a relationship with him. Stunned, he searched online and found accounts featuring his photos on Facebook, Instagram and more than 60 different dating sites.

“It was a very chilling experience,” he recalls. Together with Waters, who contacted him after a scammer targeted a friend of her mother’s using Denny’s picture, they founded the AARS. They approached the platforms concerned, but despite extensive efforts, managed to get only about a third of the fake profiles removed.

Denny is still contacted by several women each week, all trying to find out if he is the person they’ve fallen in love with. And every time he explains the situation, “I’m really breaking up with someone who had no idea they were being scammed.” It takes its toll. Some have even refused to accept the truth, believing he must be trying to hide them from his wife. The family now lives in a gated community and Denny is careful about posting pictures online.

“This will be with me for the rest of my life, and it won’t end until it’s not profitable for people to make money this way.”

West believes the ultimate way to defeat fraud is for entities “across the entire life cycle of a scam” to work together, pooling resources and sharing information. She also believes technology is being underutilized and banks need to embrace new models of fraud detection.

Bryan Denny receives three to five messages daily from women who believe they're in a relationship with him.

Thousands of fake profiles using his image have been created to date.

Sharing intelligence to defeat scammers

LexisNexis® Risk Solutions, part of RELX, is at the forefront of a new generation of analytic models that draw on data to help financial institutions identify imposter scams as they happen.

Fortunately, financial institutions are stepping up. “I see more and more financial institutions wanting to challenge the more rigid approaches that have existed in the past and use adaptive fraud models…that can quickly adjust to the types of fraud attack vectors that we’re seeing,” says Kim Sutherland, vice president of fraud and identity strategy at LexisNexis Risk Solutions. “To fight fraud, these more evolving AI-powered models are going to be really important.”

The company's cybersecurity tools include LexisNexis® Threatmetrix®, a digital identity intelligence and authentication solution that calculates risk based on signals, which are enriched by continuous feedback transaction data to increase both the accuracy of risk detection and the recognition of trusted users and credible transactions. In these instances, risk signals may show that a customer is “operating differently than they have in the past” and could be in a scam, says Sutherland.

Once alerted, financial institutions can use risk-based authentication to slow down suspicious transactions and request greater identity verification, increasing the chances of stopping fraud.

LexisNexis Risk Solutions is encouraging banks and other industries to share intelligence via its LexisNexis® Digital Identity Network®, a global consortium of anonymized data that can help identify fraudulent activity in near real time. “Often the fraudster does not operate in just one financial institution or with just one victim, and if we can help our customers to share those insights, we can better identify fraudulent activities, which is going to be super helpful in fighting crime,” says Sutherland.

Understanding the psychology of scams is also vital to those efforts, she says. “We need to continue to help educate everyone on identifying fraud and not being ashamed or afraid to report it.”

Campaigners believe momentum for action is building. Hyland has turned her devastation into activism, working with both AARS and Operation Shamrock as its Volunteer Coordinator and as part of Victim Services Unit. She is also detailing her experiences in a book, When Swiping Right Goes Wrong: Diary of a Romance Scam, so others can better understand how fraudsters work.

“No one should ever have to experience this kind of heartbreak…After it ended, I decided to dedicate my life to fighting this heinous crime.”